Protesters of the proposed Diamond Pipeline have found their voices silenced since a law signed by Oklahoma Gov. Mary Fallin took effect in May.

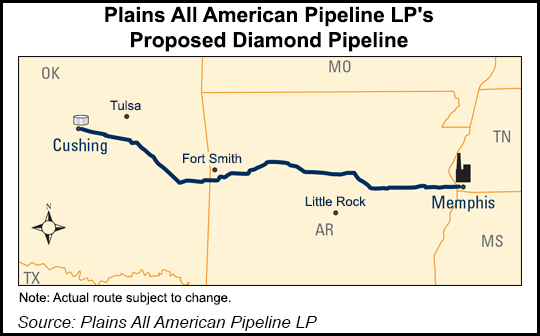

The Diamond Pipeline is being built from Cushing to Memphis, Tennessee, by Plains All American Pipeline LP and Valero Energy Corp. The pipeline’s website said construction began in 2016 and will be complete this year.

Native Americans and other groups protested the pipeline at its starting point in Cushing until a new law barred those dissenting from the land.

On May 3, Fallin signed House Bill 1123, which states that anyone accused of trespassing on “critical infrastructure” could be heavily fined.

The construction site for the Diamond Pipeline is considered critical infrastructure, which forced the protesters to leave the site, effectively ending the protest.

Protesters said the new law is meant to scare them into silence.

“I felt like (House Bill 1123) was a way to silence our voice,” said Mike Casteel, of Native advocacy group American Indian Movement. “It was an intimidation bill.”

Native Americans have three primary reasons for opposing the pipeline. First, they are angry the proposed pipeline will cover some of the land known as the Trail of Tears.

The Trail of Tears is the path that Native Americans were forced to take when the U.S. government forcibly removed tribes from their homelands in the Southeast and made them walk to Oklahoma. In digging the pipeline, Casteel said Native Americans fear that construction crews will come across the remains of those who may have died making the journey.

“It hits close to home because my family was forced to move here,” Casteel said. “We aren’t native to this land. If they were to dig up a white man’s bones, they’d go to jail. If they dig up our bones, they get rich and put it in a museum. They wouldn’t think of digging up bones elsewhere, but they don’t respect us.”

Also, Native Americans are concerned about the environmental impact of the pipeline. Protesters said neither of the companies building the pipeline has a track record of being environmentally friendly.

According to its website, the Diamond Pipeline will be built safely.

“The Diamond Pipeline is a federally regulated interstate pipeline and is subject to rigorous design, construction, operation and maintenance standards,” the website states. “Our design and construction methods meet or exceed the United States Department of Transportation pipeline standards. New pipe was manufactured to exceed industry standards and specifications. The pipeline will be laid at an increased depth to reduce susceptibility to third-party damage.”

Casteel said his group disagrees with that assessment and worries about what it believes could be catastrophic environmental damage to tribal lands.

“We have experience that tells us that almost 100 percent of pipelines fail,” Casteel said. “They weld upside down, so there is such a great risk. We want to protect the water.”

According to MySA.com, a San Antonio website, Valero Energy’s Corpus Christi refinery was sued in December 2016 because it allegedly contaminated the city’s drinking water.

Another article published by the NormanLeaks website contains a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency document showing Valero and Plains All American as two of the top three companies who had penalties for environmental violations.

“The concerns (about the pipeline) are environmental, spiritual, economic and legal,” said Ashley McCray, Native American environmental advocate.

Finally, Native Americans oppose the pipeline because it crosses their sovereign lands without their permission. Opponents of the pipeline said House Bill 1123 infringes on their rights to free speech and freedom of assembly as well as their sovereign rights over their nations’ lands.

“Every tribe has the right to be self-determined to be self-governed and be autonomous and has the right to determine what is on their tribes’ boundaries,” McCray said. “We see that with the Ponca Nation and Pawnee Nation, both tribes have passed legislation within their tribal jurisdictions that ban fracking and wastewater injection fluid from going into their tribal boundaries. But the federal government undermined their sovereignty, which is illegal and a violation of our treaty rights and basic human rights.”

Neither of the companies building the pipeline contacted any of the 39 federally recognized Native American tribes whose lands it crosses, McCray said. They instead used a loophole to get a permit to construct on the site and ignored the tribal boundaries.

“(The companies) know that the tribes are self-determined and if they consult us, they would have to take out a lot of time to talk to all of us,” McCray said. “They are interested in making money, not spending money.”

Native Americans will not give up their opposition to the pipeline because of the law, Casteel said.

“People cannot discourage us with a bill,” he said. “Water is our future, which is why we need to protect it.”